Did you know computers don’t have to be digital? Of course, you did, but I needed an intro, so here we are.

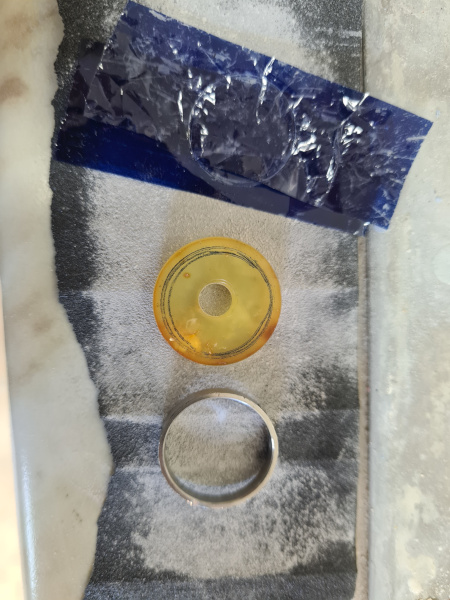

It starts with a fascination and an idea. Astronomical rings in this case. Of course, today you can buy almost anything, but never quite the way you want it.

So why not take some “junk”, or let’s call them “half products,” off the internet and make something really nice! A proper sun ring with a real “sun stone” for the gnomon.

Not to bore too much with details, since most of the work is in detailed sanding, but the whole process can be broken down into these parts.

Material acquisition:

Detailed work:

Inspection:

Testing:

Not much to say, accept the Software You Can Love conference was wonderful.

What about this weather we’re having?

Ah well, at least the laws of equal exchange agree with exchanging screen time with fresh air.

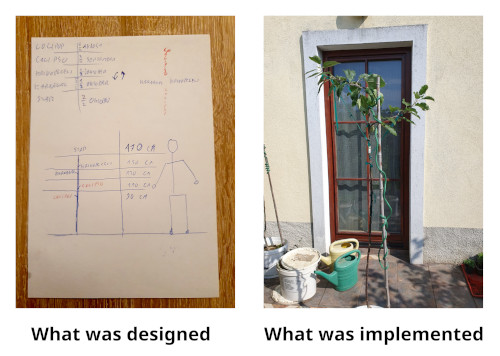

But let’s discuss balancing tree structures.

Adding new nodes and branches is usually quite a straightforward operation. Most of the time you don’t have to do anything, the structure grows on its own. But without any kind of supervision or maintenance, it will grow into a random, hard to traverse mess that just wastes resources.

So it is important to either implement proper growing algorithems into the structure itself or do some manual pruning manualy.

Now, whether it be databases or file system structures, it is best practice to do the balancing operations at off peak activity times.

And if you’re developing custom algorithms, document them! Take good snapshots of before and after states for studying.

These are definitely words in the title, but what do they mean? A long-awaited adventure!

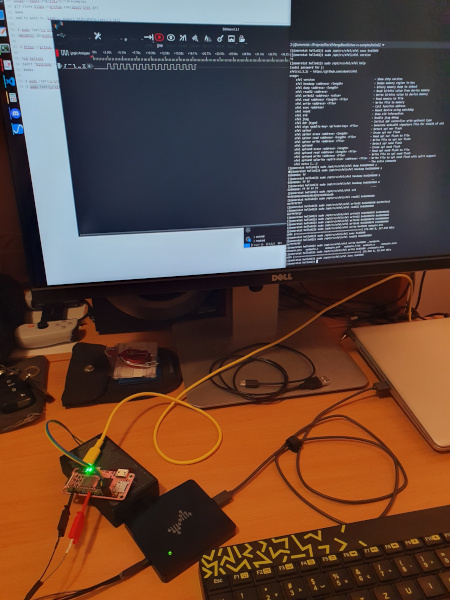

By now, the probably obsolete and forgotten RiscV version of MangoPi has been on my TODO list for a while. Fashionable late, but sometimes you have to let things take their time.

What we have here is bare bone blinking of an LED on the MangoPi SBC with Allwinner D1 RiscV chip.

Quite a few steps to get to this point, from figuring out the boot procedure, architecture, pin-out, tool chains, itd…

The condensed version of the steps and code is here.

And there might be some notes as well.

Just because nothing worth writing about is happening, doesn’t mean nothing is happening. Sometimes you just have to bear through the grind to reach a new point.

That does not mean you should completely abandon everything. Repetition keeps things in memory. So a post for the sake of the process of creating a post on this system.

So what have You done on this additional day of the year?